Jonathan Edwards’ sermon, “Sinners In the Hands of An Angry God”, provided the spark that ignited the *First Great Awakening. The Awakening, which swept the Atlantic seaboard in the early 18th century, was a *mixed blessing. Thousands converted to Christ, but the faith they embraced was an *anemic version of the sturdy Puritanism carried to American shores by the Great Migration (1630-1641). A *neo-Puritan, Edwards did more perhaps than any other to undermine the foundations of John *Winthrop’s Holy Commonwealth (a Christian state) and perpetuate the *half-way covenant. He was, in fact, expelled from his Northampton church because of his emphasis on *experientialism and insistence that children be barred from the Communion table until they could articulate a profession of faith. In his “Doctrine of Religious Affections” he defended his emphasis on religious *emotion or experience as the foundation and *evidence of faith. Thus, America was prepared theologically to accept the covenant breaking *Constitution of 1787, in which any official commitment to God as the source of *law was banned.

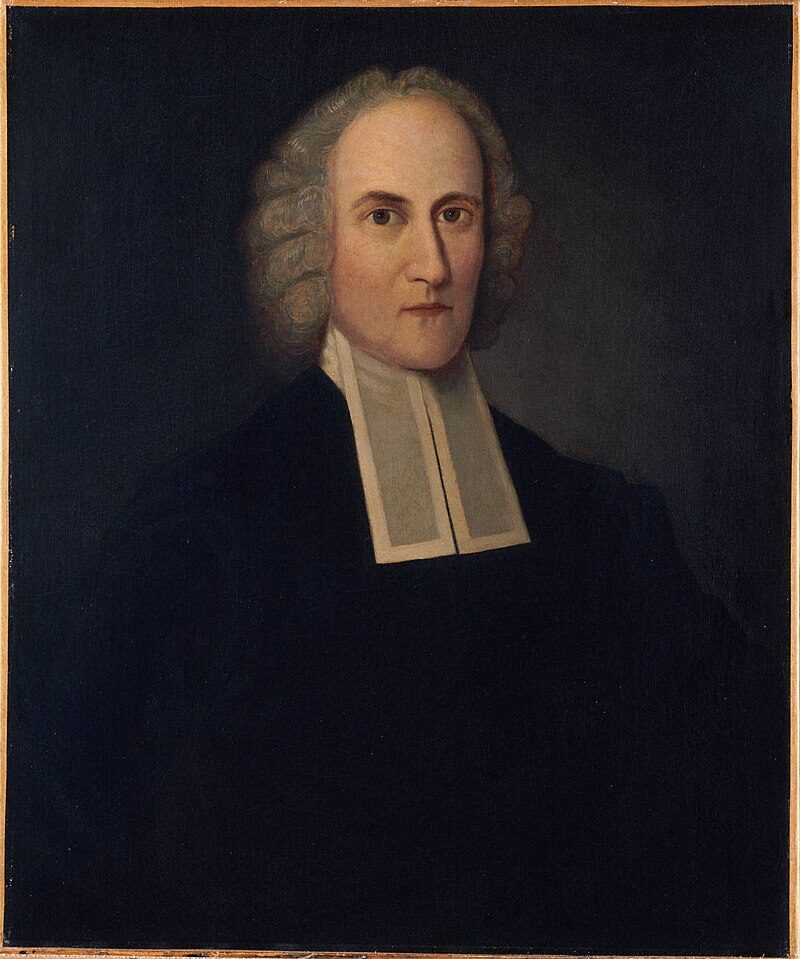

Who was Jonathan Edwards? (1703-1758) Jonathan Edwards was a Congregational clergyman and influential theologian. He was a powerful evangelist and leading figure in the First Great Awakening in the American colonies prior to the Revolution.

Historical context. Puritan New England was established as a Holy Commonwealth, in which the civil government and its leaders were under formal covenant with God to rule according to His law-Word. Almost from the beginning forces conspired to replace the Holy Commonwealth with a man-centered social contract. The impulses toward disintegration were many and diverse. Among other things they included the loss of social cohesion that came with geographic expansion from the Boston hub and other social factors such as slave trading and intolerance toward strangers. Economic impediments included the Puritan penchant for price fixing, common ownership and the 1688 decree that the franchise be based on property ownership rather than church membership. Spiritual factors such as the autonomy of Congregational church government and Cotton Mather’s promotion of Newtonian natural law and (inadvertently) Deism certainly played a role. The Halfway Covenant also produced spiritual alienation among the second and third generations because the Puritans denied the Lord’s Table to their baptized children.

Other factors were political, such as the pluralism introduced by Roger Williams in Rhode Island and universal suffrage implemented by Thomas Hooker in Connecticut. Both of these developments permitted non-believers to participate in civil leadership and ensured its eventual corruption. On top of all this, the Salem witch trials (1692) gave the Puritans a theological black eye from which they never fully recovered.

As the result of this fragmenting process, a spiritually listless and stunted church staggered out of the 17th Century into the Age of Reason. The God-fearing Puritan was fast becoming the self-sufficient Yankee. Ironically, it was an ostensibly Christian movement, The Great Awakening of the 1740s, which drove the final nails into the coffin of Puritan covenantalism. The leading figure in the Awakening was the neo-Puritan, Jonathan Edwards. The neo-Puritans, from that day to this, have retained the soteriological (salvation) distinctives of historic Calvinism at the same time rejecting its covenantal obligations to the totality of life and culture.

Summary of Edward’s teaching. The revival was kindled in 1741 by a sermon delivered in Jonathan Edward’s Northampton, Massachusetts’ church, the now famous Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God. The impact of this sermon was dramatic and immediate, effecting not just Edward’s congregation, but villages and Congregations up and down the seaboard. Sinners were smitten with conviction, groaning and crying out for salvation.

Unfortunately, Edwards mastery of biblical theology did not match his hermeneutics (preaching) nor his soteriology (doctrine of salvation). “Platonism and Locke had taken their toll in his thinking, and he wanted to substitute for the holy commonwealth the religious experience of the individual. Entrance into the church was conditional with Edwards on experience, not upon the covenant. Covenant, commonwealth and all else was dissolved by this pre-eminence of psychology. The essence of Christianity was now the religious experience. Man was religious man only when possessed by the religious sentiment or affections “ (1).

Nowhere was Edwards’ antinomian emotionalism more evident than in his pietistic Treatise on Religious Affections (1746 ). The work contains scant reference to the law of God or cultural responsibility and the words “sweet” or “affections” are found on nearly every page. The Christian faith is certainly not devoid of religious emotion, but to place sentiment at the center introduces a destructive imbalance.

Implications for subsequent history. It was ironic that the man who delivered perhaps the most powerful evangelical sermon ever written was most responsible for the acceptance of Enlightenment philosophy in North America. The inclination of many writers to describe Edwards in such glowing terms as “the greatest theologian America has yet produced” or “American philosophical genius” is indicative of the extent to which our theological discernment has been stunted .

Edwards preaching resulted in the conversion of many individual souls to Christ, although Edwards himself admitted that few of his converts persisted in the faith (2). Moreover, it yielded a relaxation of denominational barriers that permitted Americans to unite effectively against a common enemy in the American Revolution a generation later (1776). However, the anti-covenantal implications of Edwards’ theology came to fruition in the Constitutional settlement of 1787-88. There American Christians were prevailed upon by a Convention dominated by operationally unitarian lawyers to reject the national covenant with God in favor of a God-denying social compact. In that compact the authority of God was exchanged for the authority of “we the people” and the covenant oath to God was outlawed (Art VI, Sec 3). A nation’s form of government is always a reflection of its belief system. Politics follows theology as night follows day.

Attacks on the institutional church by the itinerant preachers of the Awakening resulted in national loss of respect for the church as an institution. This was accompanied in the popular mind by a transfer of legitimacy to the civil government as the primary agent of social cohesion.

Biblical analysis. To his credit, Edwards believed that the Kingdom of Christ was established at his first advent and that that Kingdom would be manifested in history before the second coming. Unfortunately, his optimistic eschatology was fatally flawed by his unwillingness to teach the rudiments of biblical law as the touchstone of cultural progress. The engine of biblical conversion is covenant commitment to the work of Christ, with emotion the caboose. As Paul declared in Ephesians 2:12, “That at that time ye were without Christ…and strangers from the covenants of promise…But now in Christ Jesus ye who sometimes were far off are made nigh by the blood of Christ.” It is that tangible covenant commitment, not the vagaries of religious experience or sentiment that defines church membership.

Corrective or Prescriptive Actions: The Great Commission will not be accomplished by the preaching of the “simple gospel” alone. Reformation does not occur by osmosis. It is not enough to assume that the conversion of individuals to Christ will eventually result in the transformation of society. The prophets of Israel called for the reformation of society in the same sermons in which they called for repentance of the individual sinner. The two must go hand in glove.