Bede is Known as “the father of English *history”, Bede reported events in Britain from the *Roman conquest in the first century until just before his death in 731. For about 200 years before the fall of Rome in *410 AD, an integrated Anglo-Romano culture prospered in the cities, but when the *Legions withdrew, Saxons from Germany took their place. Pope *Gregory sent missionaries to convert the Anglo-Saxons in 597 AD and the gospel spread *swiftly throughout Britain and Ireland. Bede not only interpreted the history of this era in his Ecclesiastical History, he interpreted the Bible in various *commentaries. Using the Bible as his frame of reference, Bede viewed history as the *progressive victory of the kingdom of God. Although he believed in a *literal approach to Scripture, he was fond of searching for *allegorical meanings beneath the surface.

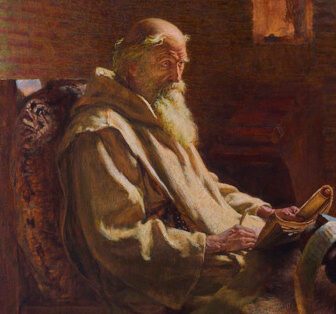

Who was Bede? (673-735) Bede was an English monk of the Benedictine order, best known today as “the father of English history,” but respected in his own era for his commentaries on the Bible. His Ecclesiastical History of the English People covers English history from the Roman conquest until 731, a few years before his death.

Historical context. Britain was conquered by the armies of Claudius I in about 45 A.D. For about 200 years prior to the Fall of Rome, a truly integrated Anglo-Romano culture developed in the towns of Britain. But Rome fell to the barbarians in 410 A.D. and nearly three centuries of darkness enveloped the former Empire. These were the true “dark ages”, that period prior to the full-blown establishment of Christianity throughout the continent. In Britain, interminable warfare between native Celts and invading German Saxons, and among the Saxons themselves, finally gave way to interludes of stability. The Saxons had been invited to Britain as mercenaries by the Celts about 515, but then led by the legendary Hengest, betrayed their employers when they failed to make payment.

The gospel first came to Britain with the missionary Augustine, sent by Pope Gregory the Great in 597. Bede relates the legend of Gregory’s taking notice of some handsome Anglo boys in the Roman slave market. “They have the face of angels,” he said, “and such men should be fellow-heirs of the angels in heaven.” Over 10,000 converted to Christ during Augustine’s first year in Britain. Fanning the flickering flame, Bede lit a candle of learning and civilization in the remote regions of British North Umbria. Working with a well-furnished library at the Wearmouth-Jarrow monastery, he wrote some 40 books on virtually every subject.

After Bede’s death, the irksome Celts who had been driven into the Welsh peninsula were finally contained by the Mercian king Offa (757-796). He constructed a huge earthen barricade extending some 150 miles known as “Offa’s Dyke” to hinder Welsh forays into Britain. (1)

Summary of Bede’s teaching. In the Ecclesiastical History Bede described an incident that illuminates the power by which the gospel conquered the Saxon chieftains. The monk Paulinus was part of a second deployment of missionaries who arrived in Northumbria in 601. After Paulinus delivered the gospel message to king Edwin, a sparrow winged its way through the hall, which inspired one of Edwin’s wise old counselors to remark,

The life of man is like a sparrow’s flight through a bright hall when one sits at meat in winter with the fire alight on the hearth, and the icy rain-storm without. The sparrow flies in at one door and stays for a moment in the light and heat, and then, flying out of the other, vanishes into the wintry darkness. So stays for a moment the life of man, but what is before and what after, we know not. If this new teaching can tell us, let us follow it.

St. Augustine (354-430) had articulated the doctrine of the sovereignty of God to include the concept of double election — to heaven and to hell — based on Romans 9 and other passages. In 529 the Council of Orange denied Augustine’s formulation. “God hath predestined no one to damnation”, said the council, and the church digressed steadily until the Reformation under the influence of Hegelianism, the denial of original sin. This doctrine was condemned as heresy at the Council of Carthage in 418, but it persisted in elevating the reason and free will of man. Bede, however, defended the Augustinian high ground in Britain (2).

The organization of time is an important aspect of man’s dominion responsibility and Bede was a master of the subject. He introduced the system of dating history before or after the birth of Christ and from this developed important historical chronology. He was fond of the theme that time is divided into six ages, based on the six days of creation and that he was living in the final age. He calculated 3952 years from creation to the birth of Christ. He wrote of lunar and solar movements, the Zodiac, various calendars and established the date for Easter.

Implications for subsequent history. In his own day, Bede had a profound influence on the Frankish king, Charlemagne, through his disciple Alcuin. His commentaries were so popular that the copyists in the Scriptorium of his monastery could not keep up with the demand. In later years, both Catholic and Protestant would claim Bede as their own, even as both would claim St. Augustine. By the 9th Century, Bede was regarded with the same veneration and authority as the four great doctors of the early church, Augustine, Ambrose, Jerome, and Gregory. He was canonized by the Catholic church in 1899.

Biblical analysis. The Bible, said Bede, “is the standard of all literacy and exegesis the central problem of all learning.” Bede interpreted history as an ongoing conquest by the kingdom, or civilization of God, fought for and won from a dark and barbaric wilderness. Adam surrendered his kingship over the earth by disobedience and Bede was convinced that his descendants would win it back by obedience. “But we for the most part have lost our dominion over the creation that has been subjected to us,” he said, “Because we neglect to obey the Lord and Creator of all things.”

Bede always let the literal meaning of the Bible text and its moral applications take precedence in his commentaries, but he was given to ferreting out numerological and allegorical meanings beneath the surface. “Whoever expends effort on the allegorical sense,” he cautioned, “should not leave the plain truth of history in allegorizing.” Nevertheless, “He defends the allegorical stretching and even wrenching of the text by an appeal to the metaphor of crushing aromatic herbs in order to release their fragrance. He works now in one system of allegorical interpretation, now in another, guided by the rule of faith, traditional orthodoxy, and Christian charity.” (3)

The general rule for explaining the figurative and analogical aspects of the Bible is to let the Bible interpret itself. For example, clearly defined anti-types in the New Testament interpret the typology of the Old Testament. Or, we would look to the Old Testament for insight about signs such as the mark on the forehead (Rev. 13:16), rather than speculating about fanciful meanings like an embedded social security number. To exceed this rule is to subject the Word of God to the imagination of man and risk adding to the Word as forbidden in Rev. 22:18.

Corrective or Prescriptive Actions. Bede was fluent in Greek, Latin and the Greek and Roman classical literature. However, his grammar text relied exclusively on illustrations from the Bible, on the conviction that Scripture should be the initial authority in the education of a Christian before turning to an evaluation of the pagan classics.